My last post mentioned the work of Lucy Hilmer, whose website shows examples of three bodies of work she made that were shot over long periods of time. Seeing her work has made me think a lot about the fact that I also have three long-term projects going that have never seen the light of day. They are: 1. My "birthday" series. Every year on my birthday I put my camera on a tripod and shoot either one roll of 36-exposure film or 36 digital images that show what I do that day from the moment I get up in the morning to the moment I go to bed that night.

2. My "post-partum" series. This series actually began while I was pregnant, when I photographed a nude self-portrait once a month for the duration of the pregnancy. I wanted to track what my body looked like as the months progressed. After giving birth, I was fascinated by the changes the pregnancy had wrought to my body, and wondered how it would age over time. So every year on the anniversary of the birth, I take a nude full-length self-portrait in front of a white backdrop: one from the front, one from the right side, one from the back, and one from the left side.

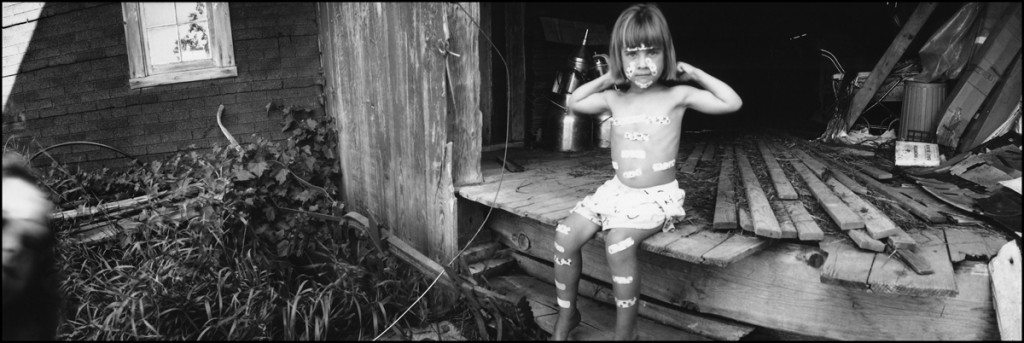

3. My "sister-in-law" series. This series started the year before my sister-in-law got pregnant. I took a shot of her in front of her house one summer. The next summer, she was nine months pregnant and I thought it would be interesting to pose her in the same spot. The next year, I thought it would be fun to pose her with her and her toddler. And all of a sudden, a series was born. All three of her children are now grown and out of the house, but every summer I am back there, posing her in front of her house, and thinking of how much time and history have passed since I started.

I haven't exhibited any of those series- I am making them just because I want to make them- but enough time has gone by now that I going to start taking a more serious look at them, both as discreet bodies of work in and of themselves, but also in comparison to each other. It's another way to discover what I have been thinking and saying as an artist over long periods of time.